The Politics of the King James Version

|

Even a king has trouble getting church members to agree.

In the early 1600s Anglicans believed the church and state should be closely aligned; Puritans, however, wanted a church independent of the state. Because James I of England had been king of Scotland, which was Presbyterian, Puritans assumed that he would support their call for reform. But James believed in the “divine right of kings”—which meant the king answers only to God and should be respected and obeyed without question. The Puritans and the Geneva Bible disagreed, which is why James thought the Puritans were “pests” and did not think highly of the popular Geneva Bible. In January 1604 James called a conference of Anglicans and Puritans “for the reformation of some things amiss in ecclesiastical matters.” Not much happened until John Reynolds, leader of the Puritan delegation, proposed a new Bible translation. James agreed immediately. “I confess,” he said, “I have never seen a Bible well translated, and the worst is the Geneva.” He knew that a new Bible translated at his direction would reinforce his image as political and spiritual leader of his people. King James appointed 54 scholars, divided into six committees to make the translation. When the committee work was finished, two members from each committee met for a final review of the entire Bible. After that, the bishops of Winchester and Gloucester reviewed the Bible, as did the archbishop of Canterbury. “There can be no question” that King James “and the bishops, scholars, and courtiers who surrounded him were all people of deep convictions, entrenched prejudices, flagrant ambitions, and committed to political ‘hard ball,’” said Gordon Baker. In spite of the claim of the title page that it was “newly translated,” the committees were specifically instructed to |

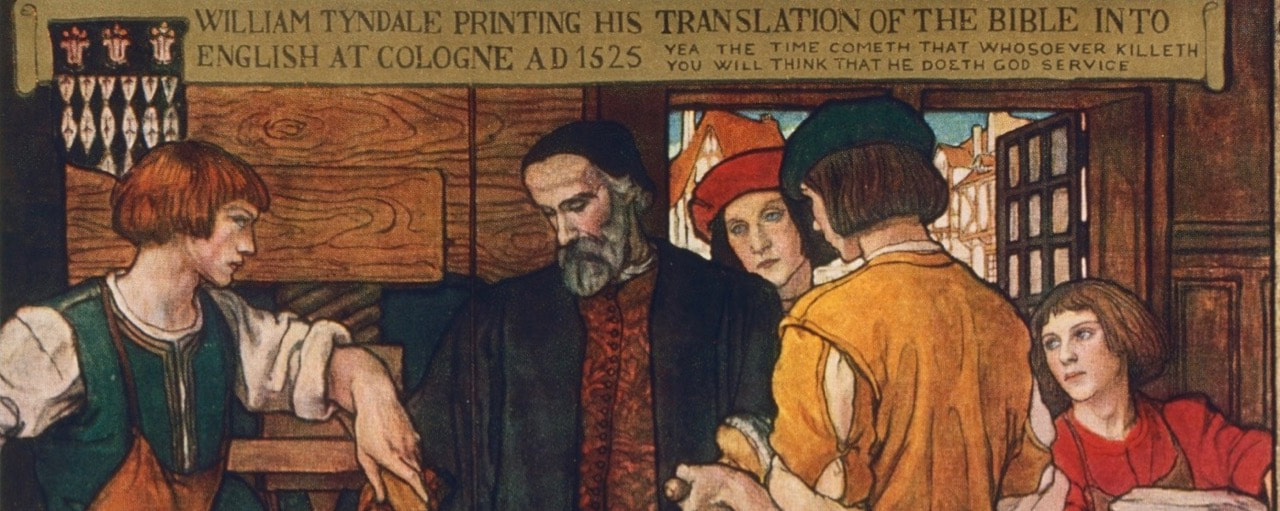

follow the Bishops’ Bible as much as possible, and to follow “these translations . . . when they agree better with the Text than the Bishops’ Bible: Tindoll’s [Tyndale’s], Matthew’s, Coverdales’s, Whitchurch’s [The Great Bible], Geneva.” In the preface the translators say they wanted to make “a good [translation] better or out of many good ones, one principal good one.”

When the six committees, twelve reviewers, two bishops, and one archbishop had finished their work, the manuscript was delivered to Robert Barker, who had a monopoly on printing Bibles in England. The first printing, which contained numerous typographical errors, was issued in 1611. James was at least more modest than Henry VIII. The only reference to King James on the title pages was that the translation was made “by his Majesty’s special Commandment.” In contrast, the most prominent figure on the title page of the Great Bible is King Henry VIII and the entire lower part of the title page pictures Henry’s loving and loyal subjects all saying, “Long live the king” (“vivat rex”). |